The Sound of Vision 1986-1992

Vision was a label project that I founded in 1986 and finished in 1992. The publications of Vision were not limited to cassettes and records but also included printed materials and visuals. These – fanzines, posters, t-shirts – like the recordings, received catalogue numbers.

Vision 1 was a zine and appeared in November 1986. While there was a subjectivist/romantic feel to it, there were also the first signs of a critical approach which later became prevalent in the label.

In a short article about Sonic Youth, for example, you could read: ‘Finally we reached the end of our cursed categories: “Punk”, “New Wave”, “Psychedelia”, “Avantgarde” etc. We are at a point where a band, in the shape of a recording or a performance, has to present an autonomous work, not to say a work of art. But the relation art – pop/pop art – rock’n’roll is already stressed, dubious. The end of this innocence certainly contributes to the general frustration, the absence of a “movement” (…) to insecurity and the well known prophecies of doom about the death of rock’n’roll, the evasion to short lived and unsubstantial revivals (…).’

Or in a review of the album 1000 Hours by the Sheffield based electronic band Hula: ‘Confusion seems complete, so that it seems doubtful that a spirit of our times will even be recognisable in retrospect’. Or: ‘The means of domination veer between conditioning and tear gas, between silent programming and pacification and if necessary the bloody subjugation of those anti-social elements that somehow eluded complete control’ in a review of Mark Stewart’s As the Veneer of Democracy Starts to Fade which was also described as ‘Dance music for our civil war parties’.

The ideas of the Surrealists, Burroughs’ Cut-Up-Methods, Industrial Culture, Post-Punk, the experiences of the bitter defeats of the early 80s squatting movement, the political reaction under Thatcher, Reagan and Kohl all came together and demanded to be processed in sound, image and word.

My first band was a trio called Flowers of Evil and we had the occasional live gigs in Basel. Soon it shrank to a duo, the drum part was played by a Roland 606 which we couldn’t properly program, so most tracks just had one drum pattern.

We played NYE at the Alte Stadtgärtnerei, a recently squatted social and cultural centre (see below for a picture from its eviction with pigs heads from an anti-ART fair installation used as missiles against the police at the eviction in 1988) and produced a cassette with four tracks which became, in May 1987, the first sonic release on Vision.

Before that, the second edition of the zine came out: “turn to crime” including the Coil interview which later became the only text from the Vision zines to be reprinted in Datacide.

Quite a few things were happening in Basel at the time. First were the singles by Les Fleur d’Hiver and Falter im nächtlichen Raum released by Winterschatten, the only underground record store in Basel at the time. Then there were more rock (or guitar pop) oriented bands such as thE silencE crieS, The Hydrogen Candymen, Man Without Future and The Baboons.

Another line of development included the releases by 16-17, U&U, Hirnschlag and Melx, which were considerably more radical and aggressive.

Seeing Melx and 16-17 live was indeed a turning point for me and for the label.

Melx – Markus Kneubühler and Alex Buess – presented what hip hop could be after Mark Stewart: no compromise hard beats, scratches, distorted vocals, a treatment of intensification, disturbing and agitational.

16-17 on the other hand created a tsunami of electric energy making you feel like being catapulted in an ejection seat. Knut Remond hammering his unique beats, Kneubühler turning the guitar into a noise machine and Buess with a screeching overblown saxophone and screamed vocal shreds.

It was only logical that Alex and I soon started working together. I became a member of Melx and we recorded a second cassette. Melx re-explored similar themes, made versions and remixes. The same lyrics were used with different beats: ‘Are you already in a Coma?’, ‘They are going to Program you’, ‘I danced with a Zombie’.

Here different principles were at work than with songwriting in a rock format. Versioning, remixing and plagiarism first rose their head in dub and early electronic dance music and would later mutate into a kind of collective cultural production in some forms of techno.

The first two records released on Vision were two albums of Fluid Mask which showed early signs of a ‘Sound of Vision’, which would be further developed with the following releases. Already then a certain tension between a more experimental approach and more traditional songwriting became increasingly evident.

Despite including a remix 12” with the second Fluid Mask album the rock structures remained initially intact, which was also the case with the later LPs by Ix-Ex-Splue and Thin King. Especially Ix-Ex-Splue had been moving towards rock music from more noisy and experimental roots, while my own interests were going in the opposite direction of electronics, noise, studio work and remixing.

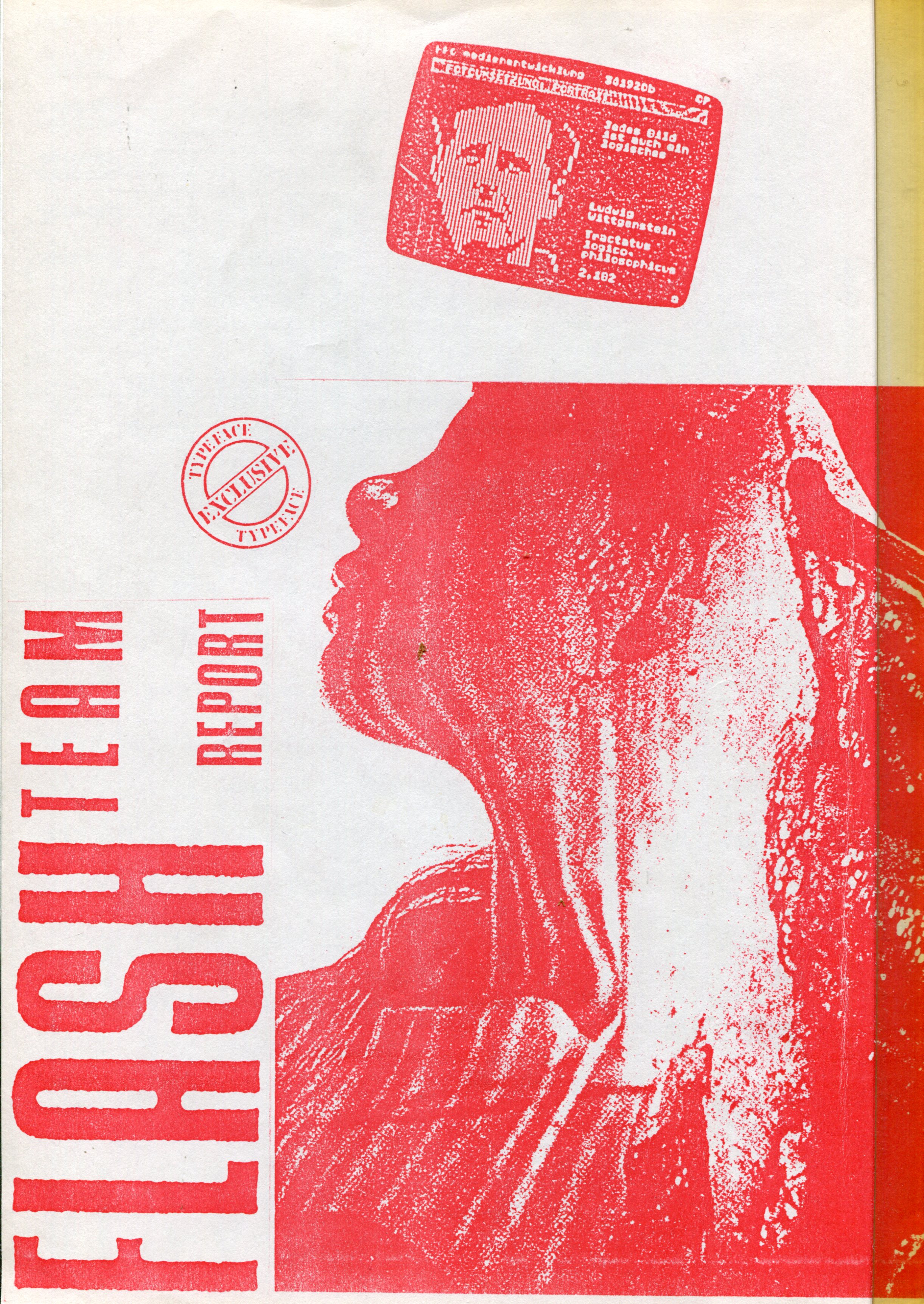

Alex Buess’ Wwolff 2.8.1. Studio was a place by the freight train station Wolf, deep underground. Concrete hallways lead to the laboratory in the bunker, far from any seasons. This was where most Vision records were produced.

The third vinyl record was The Metalhouse Masterbeats by Melx, a 4-track 12” limited to 250 copies which was conceptualised as a DJ Tool consisting mainly of beats which DJs and other producers were meant to use, abuse and develop.

Thus the record was not merely a sound carrier with superior sound quality compared to the cassette, but had its own particular properties. Alex kept upgrading the studio, adding further possibilities. One result was Victims of the Mixing Desk, where he applied radical remix concepts to previously published material from the Vision catalogue.

The studio became an instrument, the ‘Vision’ became more concrete.

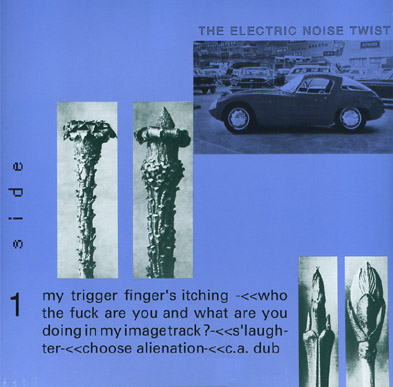

In retrospect the most convincing shape this experimenting took was in the form of the LP The Electric Noise Twist. Here elements of industrial, free jazz, noise, improvisation were combined with influences from rock and dance. The beats were played by hand, but triggered samples, vocals shouted through a megaphone, the guitar played through a Korg synthesizer and completely mutated. The procedure was largely improvised, the result still sounds intense and unique today.

By 1989, records had completely replaced cassettes. This had some serious economic consequences as well as in terms of distribution. The cassettes usually had a run of 100 copies (sometimes less) and were mostly distributed by ourselves or by Calypso Now, a Swiss tape distribution. With records both costs and ambition were a lot higher. There would be studio costs, covers were printed and the first press runs (usually 500 copies) could barely cover these expenses. Finances had to be organised, distribution extended to other countries.

With this purpose, countless contacts were established and an international network of smaller and bigger distros, fanzines and magazines were supplied with our records.

In the same year – 1989 – I started working for RecRec, the most important distributor of independent and experimental records in Switzerland. Suddenly I was in the midst of the ‘independent business’. This accelerated learning processes which in turn had effects on Vision.

As much as we tried to counter it at RecRec, the ‘independent’ market was going in a direction where it became almost impossible to subvert the market mechanisms. On the contrary, we became factors within the game and were all too often forced to throw all our weight behind ‘big’ products, while more obscure records only sold very few copies.

The ‘independent’ scene, instead of challenging the mechanisms of the music business, increasingly replicated them. This was frustrating and disillusioning.

Around that time I came into contact with Situationist ideas at first through the English underground zine Vague. I got myself a copy of Society of the Spectacle and The Revolution of Everyday Life. Here I found an encompassing revolutionary critique of modern society. With the terms ‘spectacle’ and ‘recuperation’ it grasped exactly what I experienced in the small subsegment of culture industry where I made a rather modest living at that point.

Shreds from Vaneigem, Smile and Vague started appearing in lyrics of Fluid Mask, Melx and Electric Noise Twist.

When the Neoists called for an Art Strike 1990-93, which was supposed to cause not only a breakdown of the culture industry but an intensification of the class struggle and the downfall of capitalism, I was enthusiastic and distributed countless stickers declaring ‘Just Say No To Art!’ and ‘Demolish Serious Culture!’.

Nevertheless the momentum of the label was too hard to ignore and I continued to publish cultural artifacts. Amongst them was the first and only CD to appear on Vision, Knock Out – The Sound of Vision, a compilation and stock taking with previously released material by all bands plus Hirnschlag, a project of Alex Buess from 1984 which had never been published on Vision but could be seen as a precursor.

Around the turn of the decade, the parameters of the counterculture were subject to massive changes. The relationship of ‘artist’ and ‘consumer’ in Rock’n’roll had been a one-way-communication from the stage down, something that was increasingly replicated in the ‘independent’ scene. This was fundamentally challenged by Acid House and Techno. Completely new dimensions seemed to open up for a new collective counter-culture. Anonymity, white labels, illegal parties and festivals were for me a practical application of the demand to ‘Demolish Serious Culture!’.

After I moved to South London into a squat in late 1991, the dynamic of regular collaboration and constant exchange with Basel was lacking. The Vision-scene fell apart, most bands dissolved. [The significant exception to this are the collaborations with Alex Buess in the form of the 16-17 (Praxis 31, 1999), Cortex (Praxis 48, 2011) and ‘Skin Craft’ (Praxis 55, 2016) records.]

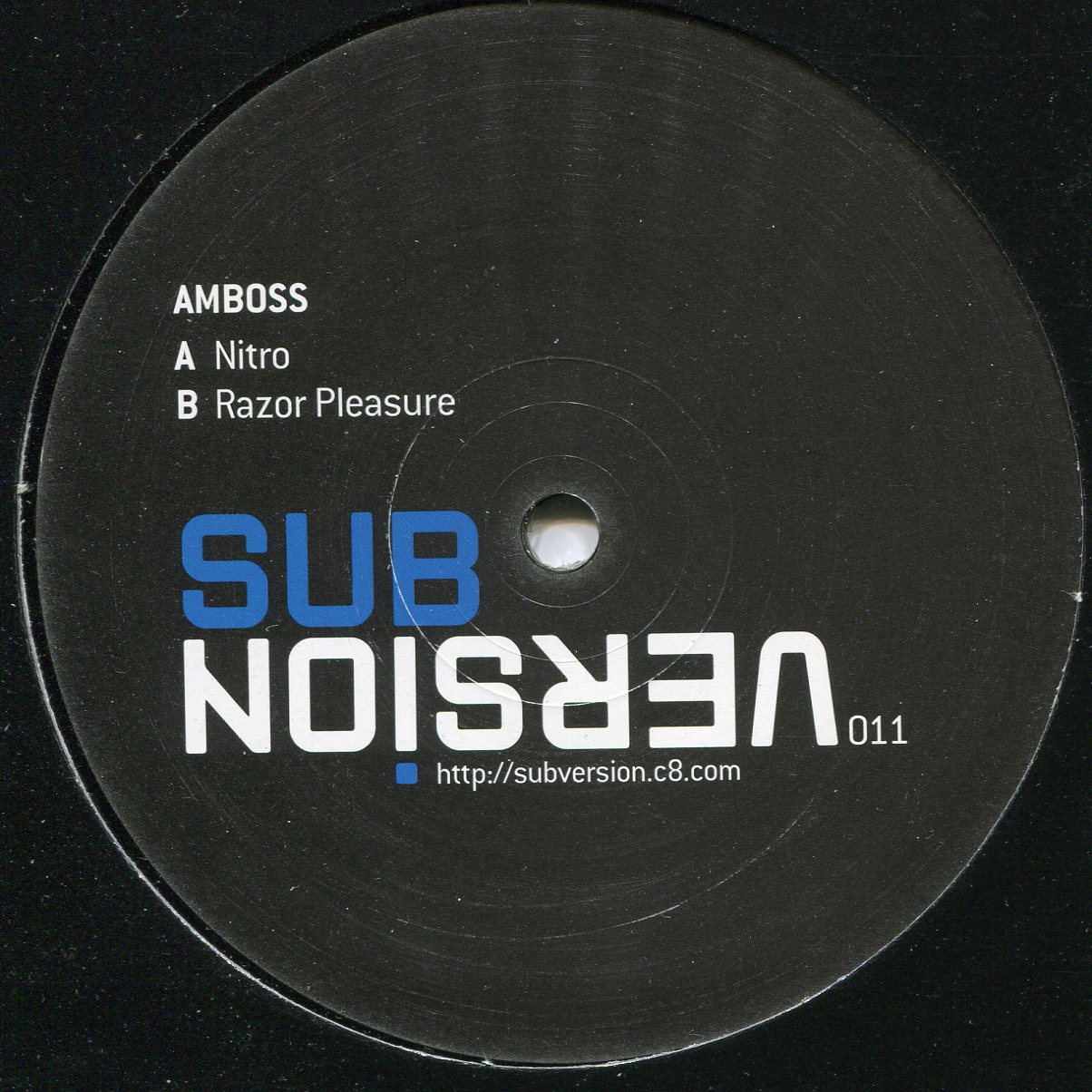

At this time I founded Praxis and Alien Underground and later Sub/Version and Datacide.

To make labels, produce and distribute records and printed matters were always methods of a cultural intervention, a metapolitical agitation.

When Melx said: ‘Magnetised human skins control the behaviour of people’, the aim was to short circuit this control and to express an antagonism towards official culture and aesthetics, towards state and capital. In the case of Vision this happened in a heterogeneous, confusing and sometimes confused way, and without a doubt all those involved had different viewpoints on this.

To me it was an intense learning process, and looking back I recognise myself much more at the end of these 5 years than at the beginning.

‘To go “further” today means to fight a guerrilla war in marginal cultural zones and to avoid a sidelining and ghettoisation as much as the cultivation of partial aspects as a reservoir of poses for the turnover of commodities’, it said in the last printed issue of Vision at the end of the ‘80s, and, ‘It’s not about the shock-value of extreme data, rather about definition; not about violence but about heightened awareness. Do everything in order not to be called as a defence witness in the case against the real world (to quote Breton). Discographies should serve as evidence in the face of this imaginary tribunal.’

Christoph Fringeli

originally written in German for

Lurker Grand/André P. Tschan: Heute und Danach – The Swiss Underground Music Scene of the 80’s (Edition Patrick Frey No121, Zürich 2012, ISBN 978-3-905929-21-8)

Translated and revised by the author for

Almanac for Noise & Politics 2016 (datacide_publishing, Berlin 2016)

Very good and informative, thanks. (why can i not type in lower case?)

Pingback: The story of Vision, pre-Praxis Records - PUNX.UK

Pingback: 16-17: Mechanophobia