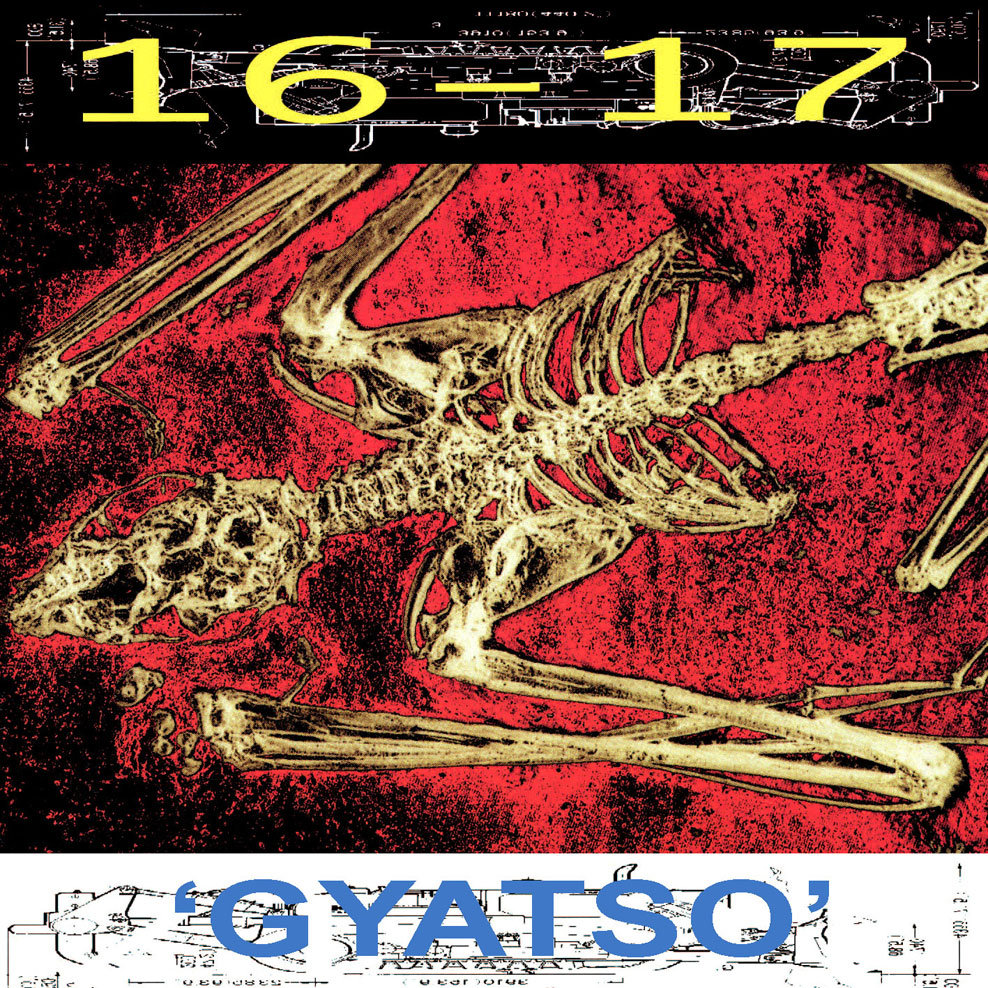

16-17: Gyatso (Liner Notes by Jason Pettigrew, 2008)

Jason Pettigrew’s liner notes which provide interesting additional information about the album Gyatso by 16-17 were originally published in the booklet for the 2008 CD rerelease on Savage Land. We republish them here in view of the forthcoming first vinyl release of the album next month.

GYATSO NOTES

Breaking boundaries? For over two decades, Swiss splatter-core outfit 16-17 obliterated the walls between so-called “exclusive” musical genres, turning the constructs of jazz, metal and punk into dust while exploring new ways to convey the urgency and power ricocheting in the band members’ skulls. Since their 1983 inception, 16-17—sax player/chairman Alex Buess, drummer Knut Remond and guitarist Markus Kneubühler—created an aesthetic that consistently delivered maximum devastation, exhaustion and catharsis.

Admittedly, you may have seen similarly toned descriptions heaped upon any number of outfits and individuals that have dared mix genres to create a new strain of aural virus. But don’t take the word of an over-zealous liner-note writer when calendars carry the ultimate truth: 16-17’s first release, the 1984 cassette, Buffbunker And Hardkore (currently available, along with the eponymous 1987 release and 1989’s When All Else Fails, in the Early Recordings set, issued by Savage Land in 2006), predates the then-nascent Downtown New York scene by five years—way before John Zorn heard his first Napalm Death record and started compacting Ornette Coleman’s repertoire into blink-and-you’ll-miss-it blasts that simultaneously offended punks and jazz purists. To his credit, Buess spent many years constructing a forward-thinking campaign of sonic evacuation—as opposed to, say, blowing his mouthpieces into Styrofoam cups of water to a rarified audience of cosmopolitan hipsters.

Although 16-17’s music was parsecs away from whatever the rest of European (FMP, ECM) and New York-based (Zzz) jazz scenes were doing, Buess wondered if the outfit had reached a creative dead end. After a 1989 tour of Germany in support of When All Else Fails, he felt the band had reached a sonic and personal plateau. From 1990 to 1994, 16-17 played few concerts, and the ennui was contagious: Remond pursued solo works and recordings with Voice Crack and Borbetomagus, while Kneubühler withdrew from playing music entirely. Buess became fascinated with recording techniques and the new digital technology (sampling, effects processing, Pro Tools and hard-disk editing) that had recently become available. He realized he had inadvertently created walls around himself in

16-17’s live-band format, but wondered what new musical dimensions he could chart by using the studio as an instrument. He began outfitting his Basel, Switzerland facility, Wolf 2.8.1., with as much new (computer workstations, digital outboard gear) and vintage equipment (tape echo units, microphones, modular synthesizers) as he could afford.

In 1993, Buess met Kevin Martin at the sessions for Liebefeld, the second album by Swiss hyper-jazz group Alboth! Martin, the British saxophonist, producer, promoter and leader of the mighty 10-piece aggregate God, helmed the sessions, while Buess was summoned to add his mercurial sax work to the proceedings. Martin was a big 16-17 fan who, over the years, had tried to contact the band, but always fallen short, thanks to Buess’ not having a fixed address or phone at the time. Nevertheless, the two musicians became friends, bonding as self-professed “sound maniacs,” who shared similar attitudes, aesthetics and approaches to music.

Their first musical foray together was recording Under The Skin, the 1994 debut album by Martin’s ad hoc dark-dub unit Ice. The sessions were significantly enlightening on both a musical and personal level that Buess asked Martin to produce 16-17’s new recordings.

“We both have similar psychological profiles and patterns,” Buess says about his working relationship with Martin. “Kevin once told me that making extreme music is like eating very hot and spicy meals: The adrenaline level rises, and you feel like burning. We want our records to be an adventure for the listener.”

“I really liked the intensity of 16-17’s early recordings,” recalls Martin. “But I felt they were more like live documents and I wanted to hear them enhanced by the power of studio layering/technology. I was obsessed by Public Enemy’s Bomb Squad production team and I felt it would be amazing to hear a free-jazz outfit given a similarly heavyweight sonic-assault treatment.”

Buess had approximately six hours of 16-and 24-track live recordings of the original trio, from which he and Martin began their editing process. Their first step was to edit and assemble Remond’s drums into loops of varying lengths. Then, at Martin’s suggestion, the rhythm tracks were shipped off to Godflesh bassist C. Christian “Benny” Green in Birmingham, to add his own

low-end theory to 16-17’s idiosyncratic skree. (Martin: “I felt he was largely underrated and Justin [Broadrick] got most of the attention in Godflesh. I felt Benny was an immense bass player and I knew he had really eclectic tastes.”) With the rhythm bed in place, Martin and Buess added Kneubühler’s already corrosive guitar work (which was further mutated by a bevy of digital effects) to the mix. Martin then dropped samples of his own design—including, but not limited to short soundtrack excerpts, orchestras,

machine sounds, sirens, the band members’ performances and voices lifted from ceremonies, loudspeaker announcements, choirs and porn videos—to add an otherworldly texture to the proceedings. (According to the production notes, the samples had file names like “Sick Animal-Eraserhead,” “Slow Motion,” “Pulp,” “Berserk Machine,” “Tribal Suicide” and “Lead Pipe Trance.”) Then, the mighty Buess—who would routinely win gold medals if circular breathing ever became an Olympic sport—played new sax parts over the constructions. The reconfiguring of the existing material via computer editing and sampling with Buess’ looming physicality made for a disc that Buess describes as “a mixture of dinosaur and rocket! We were very happy when we listened to the mixes. [The tracks] don’t sound constructed at all. It still kept the impression of live sound, but it was much more powerful.”

Looking back on the proceedings, Martin says he enjoyed his role as Phil Spector from Hell, with Buess egging him onward. “Alex was an invaluable part of my production-learning process,” he reflects. “He did seem a little alarmed by the continuously harsh use of high frequency. He’s a perfectionist and a worrier—so am I—but we were both trying to see how far we could go. We both wanted to push the boundaries of jazz, and I particularly wanted the cerebral impact to combine with an equally uncompromising physical attack. At the time, I was transfixed by the sonic sorcery that digital innovation had allowed. That, combined with the analogue gear gave the record some warmth and some completely barbaric frequency ranges.

“Alex wanted me to stoke up the fire,” he continues. “He made it apparent to me that he felt my God recordings were too laid-back. [Laughs.] I took the bait, wanting to amplify their musical rage with my dreams of a wall of noise.”

The sessions were a successful manifestation of Buess’ personal aesthetics, as well as his non-musical influences. He is fond of using the term “biomechanical”—originally coined by Swiss artist H.R. Giger, whose frequent images of chrome-plated and mechanized human decay are well known to describe the human and technological processes of the music. Likewise, Buess also cites the modern minimalist architecture of Peter Zumthor and sculptor/film director Bernhard Luginbühl as visual analogues for the disc’s raison d’etre. “[The works of these people] helped us in finding a vocabulary, an expression chart, for the production,” he says. “That’s why if you listen to [Gyatso], you’ll find all these elements as a fusion.” Clearly, the most curious of his influences shines through in the title. Buess titled the disc in homage to Palden Gyatso, the Tibetan monk who was imprisoned and tortured by the Chinese government for 33 years before human-rights activists secured his release. At first listen, one would think the title was ironic, considering all of the sonic violence contained within. Not surprisingly, Buess prefers having balls over merely being ironic. “It was a political and human statement,” he says, emphasizing the importance of the title. “We respected the great energy and intensity of this man. Gyatso is not so much about violence; it’s about energy and power.”

Released in June 1994 on Martin’s Pathological label, Gyatso significantly polarized listeners due to its sophisticated production and primitive emotional context. The opening salvo, “Attack > Impulse,” is the sound of world panic: The drums regenerate from snare rolls to Uzi fire as Buess’ sax work seemingly channels everything from dive-bombing jets to wounded animals. The rudimentary beats and pulsating frequencies on “Black And Blue” generate menace while Buess viciously tongues his reeds like a meth-addled King Curtis as the public address system in Hell’s airport instructs the damned to their final destination. “Motor” is as close as the disc gets to old school 16-17 (similar to the tracks on the trio’s self-titled release), but it remains fortified by the dense production and samples that sound like several hundred immolated orchestras. “White Out” is exactly that, a full-on mélange of sax shrieking and punishing tribal beats (or is it actually a motorcycle idling?), densely packed to approximate death by avalanche. Alternate mixes of “The Trawler” and “Motor” were added at the disc’s end to document the level of audio morphing and, according to Martin, “increase pressure on the listener.” Mission accomplished!

“It was really something that was different to what everybody was doing then,” opines Buess. “The computer technology had started to develop, but a lot of people—especially in the musical field—were still not aware of the huge amount of possibilities this technology would add to creative studio production. Gyatso was received curiously: Some people and journalists loved it immediately because of the furious energy and ‘constructive deconstruction.’ Naturally, some people hated the disc because it was too relentless.”

Martin’s take is significantly more passionate—and a lot more brusquer. “This was cyber-jazz that was virtually ignored at the time, while every critic sucked Zorn’s dick. Zorn was—and is—incredible, but Alex is a hugely underrated player, capable of amazing explosions of sound and emotion. Alex is more of a splatter technician who’s more interested in releasing his demons than shifting units. He seems to need the release more than prettying things up for the listener.”

If some knee-jerking critics decried that 16-17 had traded their soul for a body mass of integrated circuits, all bets were off in the live arena. Buess enlisted Alboth! drummer Michael Werthmüller and bassist Damian Bennett (from British doom merchants Deathless) for several tours in late ‘94 and ‘95. The trio realized Gyatso onstage with sampling technology that allowed them to replicate the disc’s punishing density and psychotropic dynamics. More importantly, the performances also raised the bar significantly in a way best described as “future primitive.” Each new performance found the trio balancing the brusque improvisation tempered by instinct and impulse (“attack” or otherwise) alongside the cerebral knowledge of operating and interfacing with the technology, and then responding to that gear essentially as a mechanized fourth member. (The band’s blistering performance at the 1995 Taktlos Festival was recorded; Buess promises its release will see the light of day.)

Gyatso sold respectably, considering how positively alien the thing sounded in a jazz climate marked by releases that were either reprehensible or simply coma-inducing. Buess had found respect from some unusual quarters, as well: Kevin Shields, the leader of renowned atmospheric guitar act My Bloody Valentine, was so fascinated by the disc that he extended an invite to Buess to join the band in the studio as programmer as they worked on what was to be the follow-up to their landmark recording, Loveless. (“I enjoyed it, but it wasn’t so productive,” recalls Buess about his month-long stint in their studio in the summer of 1995. “There’s not much more I can say about it.”)

The experience of Gyatso became a crucial first step in 16-17’s new direction. Human Distortion, a 1998 four-track EP for Alec Empire’s Digital Hardcore label, teemed with sonics both furious (Buess’ civilization-destroying sax tones) and fucked-up (samples of a television reporter delivering news of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination on the tastelessly titled “Headlead”). Likewise, Mechanophobia, a 12-inch single for the Swiss label Praxis released the following year, was impossible to get your head around at first listen, let alone getting your groove on in a dance club. But 13 years after its release, Gyatso—the original collision of worlds old and future—remains as vibrant and violent, caustic and confusing than ever. It also sounds like it was recorded last week. No small feat, considering how many of history’s genre-specific releases of an “intense” nature (punk, industrial rock, heavy metal, free jazz et al) have their own date-stamped crosses to bear.

“I’m surprised it still stands up so well,” admits Martin. “It is a difficult listen, and willfully so. But it was made to stretch the parameters of a stagnant jazz scene, where the spirit of Teo Macero could still be used to ignite reaction and demand both love and hate. No neutrality—Switzerland’s had enough of that!”

“I think all creative, innovative minds try to get as near as possible to an enhanced imagination,” offers Buess. “It does not matter by which means you reach this goal. It’s about trying to get the most out of what you can imagine. Which is why I think people like Albert Ayler, John Coltrane and Charlie Parker would have explored electronics with the same enthusiasm they had explored their instruments with during their lifetimes. If there is an urgency to express something, you’ll always find a way to do it.

“It’s all about choice,” he resigns. “If your choices are right, all the doors are open to whatever you can imagine. If the choices are wrong, everything is just meaningless and superficial.”

Jason Pettigrew

Two-Way Mirror

Cleveland, USA