Noise & Capitalism

Just received a handful of copies of this hard-to-get-by book, which includes contributions from Datacide writers such as Howard Slater and Matthew Hyland. A more critical appraisal should appear on the datacide site in due time.

(update: we no longer have any copies in stock)

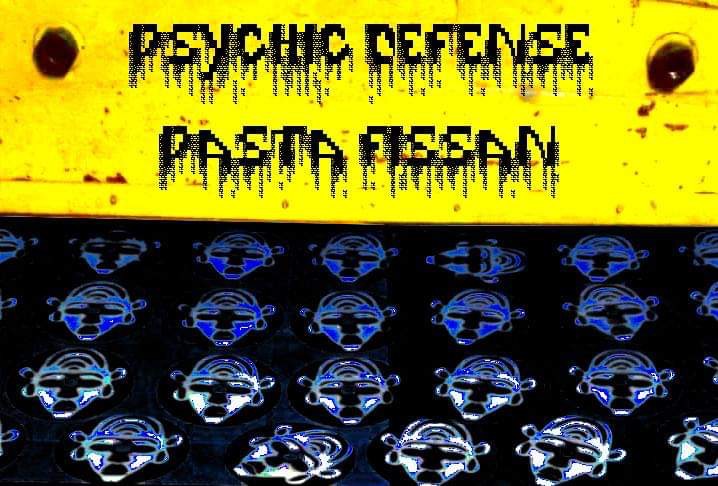

Noise & Capitalism book

Publisher: Arteleku Audiolab (Kritika series), Donostia-San Sebastián (Gipuzkoa)

Publication date: September 2009.

ISBN: 978-84-7908-622-1

Contributors: Ray Brassier, Emma Hedditch, Matthew Hyland, Anthony Iles, Sara Kaaman, Mattin, Nina Power, Edwin Prévost, Bruce Russell, Matthieu Saladin, Howard Slater, Csaba Toth, Ben Watson.

Editors: Mattin & Anthony Iles

What is Noise?

‘Noise’ not only designates the no-man’s-land between electro-acoustic investigation, free improvisation, avant-garde experiment, and sound art; more interestingly, it refers to anomalous zones of interference between genres: between post-punk and free jazz; between musique concrète and folk; between stochastic composition and art brut. – Ray Brassier

This book, Noise & Capitalism, is a tool for understanding the situation we are living through, the way our practices and our subjectivities are determined by capitalism. It explores contemporary alienation in order to discover whether the practices of improvisation and noise contain or can produce emancipatory moments and how these practices point towards social relations which can extend these moments.

If the conditions in which we produce our music affects our playing then let’s try to feel through them, understand them as much as possible and, then, change these conditions.

If our senses are appropriated by capitalism and put to work in an ‘attention economy’, let’s, then, reappropriate our senses, our capacity to feel, our receptive powers; let’s start the war at the membrane!

Alienated language is noise, but noise contains possibilities that may, who knows, be more affective than discursive, more enigmatic than dogmatic.

Noise and improvisation are practices of risk, a ‘going fragile’. Yet these risks imply a social responsibility that could take us beyond ‘phoney freedom’ and into unities of differing.

We find ourselves poised between vicariously florid academic criticism, overspecialised niche markets and basements full of anti-intellectual escapists. There is, afterall, ‘a Franco, Churchill, Roosevelt, inside all of us…’. Yet this book is written neither by chiefs nor generals.

Here non-appointed practitioners, who are not yet disinterested, autotheorise ways of thinking through the contemporary conditions for making difficult music and opening up to the willfully perverse satisfactions of the auricular drives.

For more infos about our activities, check out the Noise & Politics Linktree